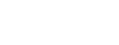

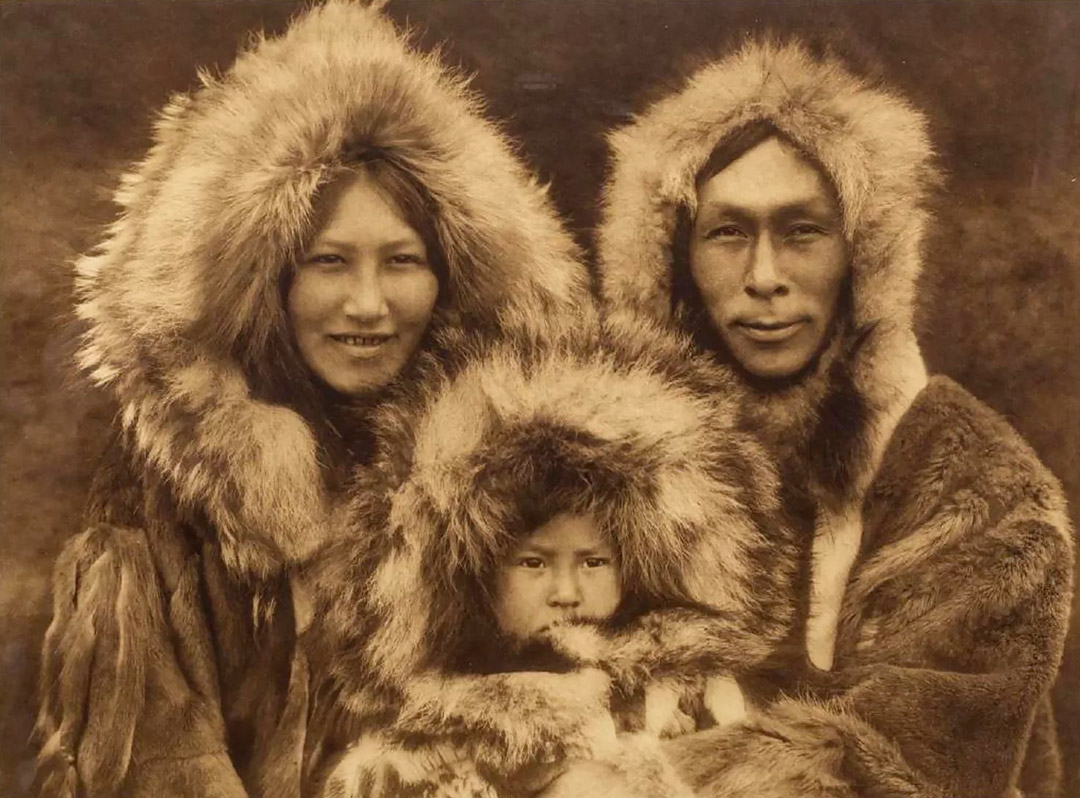

White photographer Edward Sheriff Curtis was born in 1868 in Wisconsin, and eventually moved to Washington, where he started his first photography studio in Seattle. With varying levels of accuracy, Curtis passionately dedicated his life to documenting the cultures of Indigenous peoples, at great personal cost to his family and finances. He worked with over 80 tribes, producing thousands of images, many of which he published alongside anthropological text in The North American Indian, a 20-volume portfolio set completed in 1930.

On view are rarely seen examples of his photos across many media: sepia-toned photogravures, platinum prints, sliver gelatin prints, cyanotypes, and orotones (goldtones), a process perfected by Curtis. The exhibition also includes one of Curtis’s cameras, lantern slides he used in multimedia lectures promoting his project, audio field recordings of languages and songs made on wax cylinders, and a projection of his docu-drama feature-length film made in British Columbia, In the Land of the Head Hunters (1914).

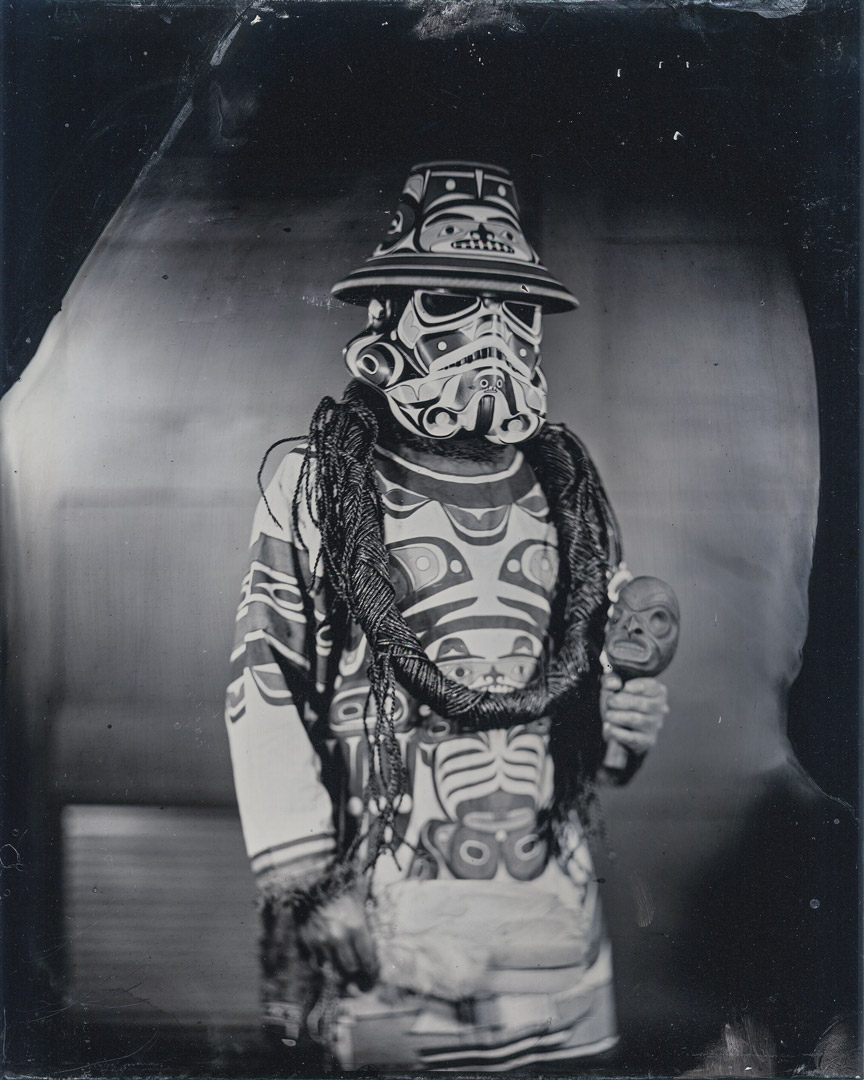

The images Curtis created continue to affect Indigenous peoples today in positive and negative ways. His records of traditional life are deeply valued by those who use the photographs and accompanying text to reconstruct cultural practices and remember ancestors. However, Curtis’s artworks reflect his personal biases, and he often staged his portraits to reflect the misguided belief that Native peoples were incapable of survival in the modern world and were a vanishing race.

Double Exposure gives us a chance to examine Edward Curtis’s legacy with a fresh lens, to learn from and contend with his images, and then to move forward. One hundred years ago Curtis was in the middle of creating The North American Indian, and his photographs still occupy a powerful place in the American consciousness. I hope that in another 100 years his pictures will be a distant memory, replaced by new visions of Indigenous identity created within our own communities. The three Indigenous artists in the exhibition are making work in spite of, not in response to, Edward Curtis. All the same, to view their contemporary works alongside those of a photographer who believed we were on the brink of extinction is a powerful gesture toward healing, and proves the adaptability, resilience, and strength of Native peoples past and present.