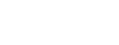

Will Wilson is a Diné cultural practitioner working primarily in photography. His work is informed by the history of portraiture and Indigenous representation in American art. He was born in San Francisco, spent his formative years on the Navajo Nation Reservation, and currently lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where he works as an artist and educator. Wilson is part of the Scientists/Artists Research Collaborations (SARC), which brings together artists interested in using science and technology in their practice with collaborators from Los Alamos National Laboratory and Sandia Labs as part of the International Symposium on Electronic Arts. In 2012, he initiated the Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange (CIPX), collaboratively creating portraits of Indigenous artists, educators, and community activists using an early photographic wet plate process.

I was lucky enough to have the chance to experience Will Wilson’s work firsthand when he brought CIPX to the Seattle Art Museum in November. He walked me through each step of the process as he made my tintype portrait, and in the darkroom we watched as the excess silver finally washed away to reveal an exposure. Experiencing Wilson’s work feels like time travel. Unlike most photographs, the image on a tintype is reversed, like looking in a mirror. Through the patina the century-old process leaves on the image, I recognized myself, but simultaneously felt like I was looking at a portrait from another time. Seeing myself captured in that way humanized past generations, and reminded me that future ones will one day examine the modern images we are currently creating of ourselves.

The Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange takes the historic tintype photographic process that was once used to objectify Indigenous peoples and reclaims it as a tool for Indigenous self-representation. Wilson has now created over 2,000 photographs using this method. On view in Double Exposure are new portraits Wilson produced of local community members, including a descendant of Chief Seattle, and influential creatives from urban and reservation communities. “Talking” tintypes, created using augmented reality, show the sitters dancing, singing, and speaking to us—a far cry from the stoic silence in many Curtis portraits.

About the author nataliw

-

October 31, 2016

-

October 30, 2016

-

October 30, 2016

All posts by nataliw →Edward S. Curtis

Marianne Nicolson